| Search This Site |

| Table of Contents |

| Home |

| Street Map |

| Church Services |

| Church Officials |

| Church History |

| Our Beliefs |

| 39 Articles |

| Declaration |

| Law & Prophecy |

| Historical |

| Evangelical |

| National Message |

| Books |

| Links |

| E-mail Us |

by kind permission

Covenant Books

OUR NATIONAL LITURGY

The

Book of Common Prayer

By

ALFRED W. FAITH

| "Come, let us worship and bow down; let us kneel before the Lord our Maker, for He is our God." |

| Venite, Psalm 95: 6-7 |

| "Open Thou mine eyes that I may behold wondrous things out of Thy law." |

| Psalm 119: 18 |

In AD. 1549 the Act of Uniformity was passed by the English Parliament, which gave us the first Prayer Book for use in the National Church. The Act was changed in AD. 1552. The Book was again revised in AD. 1662, but none of the changes at that time altered any of the Doctrines contained in the previous revision.

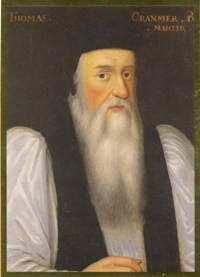

The continuity of our National Church is seen in Archbishop Cranmer's statement to Parliament in AD. 1549 that the Prayer Book, then being authorised, contained the same prayers that had been in use in Britain for over 1,500 years — that is from the days of Joseph of Arimathea and the Apostles. (The British Reformers, Vol. VIII, p.271. Also Proceedings in the House of Lords, British Museum.)

Contents

Our National Liturgy

The Book of Common Prayer

The Sabbath

The Liturgy

The Psalms of David

The Holy Trinity

The Litany

The Collects, Epistles and Gospels

The Holy Communion

Solemnisation of Matrimony

A Commination

A Form of Prayer with Thanksgiving

APPENDIX 1: The Sabbath Day

APPENDIX 2: The Calendar

OUR NATIONAL LITURGY

THE BOOK OF COMMON PRAYER held a great fascination for me long before I was blessed with the vision of Israel in continuity. The beauty of its prayers and petitions, their wonderful phrasing and choice of wording, comparable with the literature of the Authorised Version of the Holy Bible, has long appealed to me; but when I came to the knowledge, through the Israel teaching, that we, the British people, are the people to whom this book is addressed, I was simply enthralled. I could see that here we, the British people, had a heritage second only in importance to that other great heritage, the Holy Bible. As my eyes gradually became opened to the wonder and beauty of the Prayer Book, I felt convinced that none other than holy men of God, moved by the Spirit of God, could have been used in its compilation; and that, like the Holy Bible, it is divinely inspired.

The Book of Common Prayer should be an affirmation of our national faith. It is designed with the purpose of bringing us to the knowledge and love of the God of Israel and our Redemption. At the same time it is designed to bring the whole of mankind to the knowledge of the saving grace of our Lord Jesus Christ.

I mention the latter especially, for although the chief purpose of this booklet is to emphasise the Israel content of the Book of Common Prayer, this does not mean to say that its prayers are not common to all people, no matter of what race or nationality; for the words of the opening prayer of the book are spoken of mankind at large: 'When the wicked man turneth away from his wickedness that he hath committed, and doeth that which is lawful and right, he shall save his soul alive' (Ezekiel 18:27). But when Israel is addressed, the language will be found to be direct and particular. For example: 'When your fathers tempted Me, proved Me, and saw My works. Forty years long was I grieved with this generation' (Venite).

In the prophecies of Isaiah we read: 'Also the sons of the stranger, that join themselves to the Lord, to serve Him, and to love the name of the Lord, to be His servants, everyone that keepeth the Sabbath from polluting it, and taketh hold of My covenant; even them will I bring to My holy mountain, and make them joyful in My house of prayer: their burnt-offerings and their sacrifices shall be accepted upon Mine altar: for My house shall be called a house of prayer for all people. The Lord God which gathereth the outcasts of Israel saith, Yet will I gather others to him, besides those that are gathered unto him' (Isaiah 56:6-8).

If then, as Israel, we are to be a blessing to all the families of the earth (Genesis 12:3), it is only appropriate that provision should be made for the stranger to share in our national worship: 'When Thou hadst overcome the sharpness of death: Thou didst open the Kingdom of Heaven to all believers' (Te Deum).

A. W. Faith

THE BOOK OF COMMON PRAYER

THE BOOK OF COMMON PRAYER was published in March AD. 1549. The preface states that, with the exception of minor and unavoidable alterations, the book today is the same as the original service books; and Archbishop Cranmer at that time, as we shall see later, offered to prove that its contents were the same as had been in use in the Church for 1,500 years past. In its origin, therefore, and for a vast period in the previous life of the nation, even during the time the Roman Catholics were the one and only body of dissenters from the Church of England, the Book of Common Prayer held the position of second only to the Holy Bible. In relation to man and his Maker, it is claimed to be the most useful, pure, simple, and important of all books of devotion, and is enjoined by the current laws of the land.

It seems to be the opinion of a large number of people that in the early days of the Christian Church there was no set form of worship; many people think that a few simple prayers were used, that these were added to from time to time as the need arose, and that it was not until the sixteenth century that an effort was made to provide the Church with an organised form of worship. This, however, is not in accordance with the facts. Our Book of Common Prayer is an ancient book, and, as we have said, its use can be traced back to very early tines.

From the early days of the Christian Church, and ever since the Apostles founded the Church in these islands, there has been an outward and visible Church in Britain, the ministers of which kept the Apostolic Faith pure centuries before the arrival of the Italian mission under St Augustine. It was not until some centuries after their arrival here that the English Church and nation became contaminated and saturated with Romish doctrine and ritual. This reached its climax during the reign of King John, who came to the throne in AD. 1199, and who, in AD. 1213, consented to hold England as a vassal of the Papacy, and to pay the Pope 1,000 marks for the privilege of doing so.

The great English historian, Lord Macaulay, says in his History of England: 'England fell (in AD. 1199) under the dominion of a trifler and coward.' About a century and a quarter later God raised up two great reformers whose work was designed to prepare the way for the loosening of the hold that Rome had fastened upon our country and upon our Church. In AD. 1325 was born John Wycliffe, the 'Morning Star of the Reformation,' who, in AD. 1382, gave to the people the Bible in their native tongue, so that all should have knowledge of the love of God and their Saviour Jesus Christ. At the same time, another reformer, in the person of King Edward III, set about taking steps toward sweeping away Papal jurisdiction from the Church; but it was not until some 140 years later that a determined and successful effort was made to rid the country of the influence that Rome had fastened upon us.

In the reign of Henry VIII there came from Rome an urgent proposal for reconciliation between Henry and the Church. Prior to this, the Pope had made Henry 'Defender of the Faith.' It is not necessary to enquire into the origin of the causes of the King's quarrel with the Pope. But God overrules even the wickedness of man to further His own purposes. Henry received the Pope's message with contempt, repudiating the authority of Rome, and declaring that he would be master in his own country in every matter, sacred as well as secular; and that he, not the Bishop of Rome, had jurisdiction over England, and over all its estates. This happened in AD. 1527. Henry followed up this declaration by forcing the convocation of Canterbury to acknowledge that he, King Henry VIII, was the supreme head of the Church and clergy in England. That there should be no question about the matter, a Bill was brought before Parliament to do away with the usurped authority of the Romish Bishops. This passed both Houses in AD. 1531, and the King's supremacy was acknowledged by an Act of Uniformity. The preamble of this Act contains the following strictures on the Pope, showing that whatever Henry's shortcomings, he was conscious that the voice of the Church of Rome was not the voice of God. The Bill says: 'The Bishop of Rome, whom some call Pope, has long darkened God's Word, that it may serve his pomp, glory, avarice, ambition, and tyranny, both upon the souls, bodies and goods of all Christians; excluding Christ out of the rule of men's souls and princes of their dominions, he has exacted in England great sums by dreams, vanities, and other superstitious ways. Upon these reasons his usurpation has been by law put down in this nation.'*

The King's next act was to purge the Service Book of the Church, though at the time the purge seems to have been limited to the suppression of all references to the Pope's jurisdiction or existence. Several years later and towards the end of his reign he instructed Archbishop Cranmer, whom he had appointed Archbishop of Canterbury, to make a further and thorough cleansing. This, however, was not completed until two years after the death of the King. During the short reign of Edward VI the work was completed and sent to Parliament for approval. This was given in AD. 1549. The Encyclopedia Britannica, Vol. VIII, 9th Edition, under Article 'England,' states: 'In AD. 1549 an English Prayer Book, carefully drawn up from old service books by a body of Divines, accepted by Convocation and Parliament, was given to the Church, and the use of it was made compulsory by an Act of Uniformity. . . . Archbishop Cranmer, zealously bent on the work of the Reformation, earnestly invited all the most distinguished foreign reformers to visit England, so that, if possible, the lovers of reformation might agree to a confession of faith, to be opposed to the confession of the Romish Church then being formulated and settled at the Council of Trent.'

In order to meet the twofold witness required by the Scriptures (Deuteronomy 17: 6), we have the following taken from Vol. VIII, The British Reformers, p. 271 : 'At this time (AD. 1549) Archbishop Cranmer asserted before Parliament that in the Prayer Book which he asked might be authorised by that body for general use in the Church of England were the same prayers which had been in use in Britain for over fifteen hundred years. . . ' I will, by God's Grace, defend not only the common prayers of the Church, but also the doctrine and religion set out by our said Sovereign Lord, King Edward VI, to be more pure and according to God's Word than any other that has been in use in England these thousand years. . .' The same doctrine and usage is to be followed which was in the Church fifteen hundred years past, and we shall prove that the order of the Church set out at this present in this realm by an Act of Parliament is the same that was used in the Church fifteen hundred years past'

The foregoing was substantiated by the late J. Harrison Hill, of the Research Department, B.I.W.F., who stated: 'Cranmer's place as Archbishop was The House of Lords and his statement will be found in "Proceedings in the House of Lords," a folio volume in the downstairs library of the British Museum.'

To bring forward yet another witness. In the introduction to Dr. Alfred Barry's Teacher's Prayer Book (1st Edition) we read: 'The English Prayer Book embodies in tangible form the chief principles of the English Reformation. It was no new book drawn up by the religious leaders of the sixteenth century, but was mainly a reformed re-publication of those old service books which had grown up through nearly a thousand years of English Christianity, being themselves developments of the liturgies of an even remoter antiquity.' (Italics ours.) .

When King Edward VI died in AD. 1553 Queen Mary came to the throne, put aside the Book of Common Prayer, and restored the old Roman Catholic service book; but she died five years later. She was succeeded by her sister, Queen Elizabeth. One of her first acts on coming to the throne was to restore the Edward VI Book of Common Prayer and make its use compulsory in the Church of England by an Act of Uniformity. Only minor alterations have since been made, so that our present Book of Common Prayer is substantially the same as the one cleansed and revised by Archbishop Cranmer and authorised for use by King and Parliament in the reign of King Edward VI.

Mention has been made that Archbishop Cranmer stated before Parliament in AD. 1549 that he was prepared to prove that the Book of Common Prayer had been in use in the Church fifteen hundred years past; this takes us back to AD. 49, the very day of the early Church, and to the time of the Apostles themselves. We may say, then, that our Book of Common Prayer was in being in the days of the Apostles and that it was authorised by King and Parliament as the nation's manual of worship, based, as Archbishop Cranmer stated, on the pure Word of God, and therefore of Divine origin.

Thus the Book of Common Prayer is not solely of ecclesiastical authority. It follows, then, that the Sovereign is the head of the Church. This is recognised in the Royal Declaration to the 39 Articles of Religion, where it is stated: 'Being by God's Ordinance, according to Our just Title, Defender of the Faith, the Supreme Governor of the Church, within these our Dominions. We hold it most agreeable to this Our Kingly Office and Our Own Religious Zeal, to conserve and maintain the Church committed to Our Charge in the Unity of True Religion, and in the Bond of Peace.' Notice the opening words of this declaration: 'Being by God's Ordinance. . .' Does this not show that the early revisers of our Book of Common Prayer were aware of our Israelite origin? It fits in so well with the Scripture, for only to the earthly head of the House of David, to which our monarchs belong, had been committed the sole privilege and responsibility of keeping pure the Christian Faith.

Frank O. Salisbury, in his book Portrait and Pageant, describes his painting of the Coronation scene. He says: 'His Majesty pointed out that the Colobium-Sinbonis, the under-tunic in which he was anointed King, must show in the picture, as it had a great significance, indicating that he was head of the Church. The garment symbolises His Majesty's priestly functions and represents our Lord's clothes after they had cast lots for His garments at the Crucifixion.'**

* Cobbett's Parliamentary History

** Youth Message, December, 1944

THE SABBATH

'REMEMBER the sabbath day, to keep it holy' (Exodus 20: 8). 'Wherefore the children of Israel shall keep the sabbath; to observe the sabbath throughout their generations, for a perpetual covenant. It is a sign between Me and the children of Israel for ever' (Exodus 31: 16-17). A distinctive and indelible mark, the ordinance of the Sabbath, has been put upon Israel by the God who declares: 'For I am the Lord, I change not; therefore ye sons of Jacob are not consumed' (Malachi 3:6), to be a sign in perpetuity that He is their God, and that they are His peculiar people; no nation outside the fold of Israel can possess that Divine token or the Sabbath ordinance, because the ordinance is the sign, the token of Israel's identity. How enlightening this is on the question of Israel's present-day identity! Let the reader ask himself not how many individuals abuse the Sabbath, but how many nations have its keeping inscribed upon their Statute Book?

There is no doubt that the Anglo-Saxon peoples have been the custodians of the Sabbath, just as they have been of the Bible. 'If you refrain from doing your own business upon the sabbath, on My sacred day, and hold the sabbath a delight, and the Eternal's sacred day an honour, not following your own wonted round, nor doing business, and not talking idly, then you shall have delight in the Eternal's favour, for He will let you hold the land in triumph, enjoying your father Jacob's heritage: so the Eternal Himself promises' (Isaiah 58:13-14, Moffatt). The Book of Common Prayer, in due conformity, requires that, prior to Confirmation, 'so soon as children are come to a competent age, and can say in their Mother Tongue, the Creed, the Lord's Prayer, and the Ten Commandments: and can also answer to such other questions as this short Catechism; they shall be brought to the Bishop.' By this means the children come under the ordinance of the Sabbath Commandment.

Surely the guiding hand of God is discerned throughout the Book of Common Prayer. The blindness of the people would be unexplainable if it had not been foretold in the Scripture that Israel, under their new name 'British,' would for a long while be unaware of their Israel nationality. 'And I will bring the blind by a way that they knew not; I will lead them in paths that they have not known' (Isaiah 42: 16). 'Bring forth the blind people that have eyes, and the deaf that have ears' (Isaiah 43:8). 'For I would not, brethren, that ye should be ignorant of this mystery, lest ye be wise in your own conceits; that blindness in part is happened to Israel, until the fulness of the Gentiles be come in' (Romans 11:25).

THE LITURGY

THE Liturgy of the Book of Common Prayer is the Liturgy of one people, and one people only, namely Israel. The book becomes meaningless unless used by members of the Israel family. The whole structure of the book is orientated to Israel, and it abounds with affirmations that we are God's servant people. The opening prayers, taken from the Prophets, the Psalms, and the New Testament, are all prayers alluding to the Israel people. To quote one: 'To the Lord our God belong mercies and forgivenesses, though we have rebelled against Him; neither have we obeyed the voice of the Lord our God to walk in His laws which He set before us' (Daniel 9:9-10). Then in the General Confession we declare: 'We have erred and strayed from Thy ways like lost sheep, we have offended against Thy holy laws' — which were given to and practised by Israel only. In the Absolution the minister says: 'God hath given power and commandment to His ministers to declare and pronounce to His people being penitent the absolution and remission of their sins.'

In the Venite we declare: 'For He is the Lord our God; and we are the people of His pasture and the sheep of His hand.' In the Cantate we thank God for 'remembering His mercy and truth toward the House of Israel.' In the Nunc dimittis we declare: "Mine eyes have seen Thy salvation, which Thou hast prepared. . . to be a light to lighten the Gentiles, and to be the glory of Thy People Israel.' Surely the British are the people here directly addressed — addressed as Israel — and, what is more, as the House of Israel.* In the Te Deum we pray: 'O Lord, save Thy people and bless Thine heritage.' Again in the Jubilate we declare: 'We are His people, and the sheep of His pasture.' In the responses we use the terms 'Thy people,' 'Thy chosen,' 'Thine inheritance.' All these names, used in our Morning and Evening services, are terms exclusively selected and given by God Himself to His own Chosen People Israel; yet the early revisers of our Church service selected them for British Christians and believers, for use in their national worship. What is the meaning of this most wonderful and curious arrangement? Let God Himself supply the answer: 'Who is blind but My servant (Israel)' (Isaiah 42:19).

Again our national faith is founded upon the Abrahamic Covenant. In the Benedictus we call upon God to: 'Perform the mercy promised to our forefathers; and to remember His holy covenant; to perform the oath which He sware to our forefather Abraham. . .' Then in the Magnificat: 'He remembering His mercy hath helpen His servant Israel, as He promised to our forefathers, Abraham and his seed, for ever.'

What are we to say, then? That the Members of Parliament who authorised its use, and the holy men who revised it, were so devoid of common sense as to sing the songs and laud the national heroes of a foreign people?

At the Morning service we sing yet another Israel song, the Benedicite. This canticle is taken from the Apocrypha, and is found under the heading of 'The Song of the Three Holy Children.' It is part of the song of thanksgiving of Daniel's three companions for their deliverance from the fiery furnace.

In the third collect for the Evening service we have a beautiful prayer, which must have been used frequently during the dark days of war. 'Lighten our darkness, we beseech Thee, O Lord; and by Thy great mercy defend us from all perils and dangers of this night, for the love of Thy only Son, our Saviour, Jesus Christ.' How prophetic that the compilers of the Book of Common Prayer should have seen the necessity for such a prayer, for at what other period of our history has it been so needed to pray to be defended from perils and dangers of the night as during the last generation.

*It is very evident that the remnant of the House of Judah and those proselytes who remained in Palestine cannot be the House intended, nor can they possibly be included, for Christ is to be the glory of Israel, whereas He is the shame of the Jews.

THE PSALMS OF DAVID

AT both Morning and Evening services great use is made of these Israel Psalms. What enrichment they have made to our worship, what wonderful thoughts they bring to our minds, as we sing them week by week in our National Church. Psalms written by the founder of the House of David, not the House of Aaron; they come from the throne, not from the priesthood. There has never been anything written like them. What a wealth of prophecy, prayer, praise, confession, and thanksgiving they contain. What a help, too, they must have been to the penitent sinner, for David does not hide his sins and weaknesses, but lays bare his soul, and tells how he found peace and forgiveness.

THE HOLY TRINITY

FREQUENT use is made of the words 'Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost; as it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be, world without end, Amen.' Why should we be so frequently reminded of God's beginnings? Is it not because 'I am the Lord, I change not; therefore ye sons of Jacob are not consumed' (Malachi 3:6). Every time we use these words we give glory and worship to the Holy Trinity, for the assurance that God has not changed His purpose. Israel was His instrument in the beginning, at the present time, and ever shall be.

Another interesting and important point is that reference to the Holy Trinity is made in everyone of the many services of the Book of Common Prayer, also in the three Creeds and in the Te Deum, and after each Psalm and Canticle in the Morning and Evening services, either in the words 'Glory be to the Father, etc.' or in some like manner.

Does this not show how fundamental the worship of the Holy Trinity is to the Christian Faith? That this is so is recognised in the Book of Common Prayer, for the very first of the 39 Articles of Religion is that of faith in the Holy Trinity, and in the Creed, commonly called that of St. Athanasius, we have the doctrine of the Holy Trinity set forth. Although the fact of God's unity and threefoldness is so well reasoned out in the Athanasian Creed, and definitely declared in the first article of religion, yet we are bound to confess that this most ancient of mysteries is beyond our understanding. In the divinely-inspired phrases of the Creed we are given as much as our finite minds can grasp; not that we should fully understand, but in order that we might see, in St. Paul's words 'through a glass darkly,' the Majesty, Might, Glory and Wonder of Almighty God, in order that we might worship Him. For as the Creed says, the Catholic Faith is this: 'That we worship one God in Trinity and Trinity in Unity.'

Thus, though we finite beings cannot fully apprehend what the Infinite Being is, we may and should apprehend Him by what He does. Every earnest Christian knows what it is to live and move in the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, the love of the Father, and the fellowship of the Holy Ghost; and this realisation should make us sure of God's existence and glory, and our own continued existence in and with Him. For what is the Holy Trinity but the power of love, outworking from the Divine into the human society. The love that comes, which is the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ; the love which gives, which is the love of the Father; the love which abides, which is the fellowship of the Holy Ghost; not three loves but one, for God is one. Thus through grace given to us we are able to worship the Holy Trinity.

THE LITANY

THIS is the most comprehensive of all the prayers of the Book of Common Prayer, embracing all sorts and conditions of men. Firstly it is a prayer of a redeemed people, therefore an Israel prayer supplicating Divine forgiveness of our own especial sins. 'Remember not, Lord, our offences, nor the offences of our forefathers; neither take Thou vengeance of our sins; spare us, good Lord, spare Thy people, whom Thou hast redeemed with Thy most precious blood, and be not angry with us for ever.' Secondly, we have Israel supplicating Divine blessings on all the nations and families of the earth: 'That it may please Thee to give to all nations unity, peace and concord.' 'That it may please Thee to have mercy on all men.' Then we pray: 'O God, we have heard with our ears, and our fathers have declared unto us, the noble works that Thou didst in their days, and in old time before them.' What more noble works are there on record that come to our mind that God did before the dawn of Christianity than those recorded in the Old Testament Scriptures for His own people Israel? How meaningless this prayer becomes if we follow the teaching, so prevalent at the present day, of laying aside the Old Testament Scriptures on the grounds that the 'noble works' recorded therein are but myth and legend!

We pray: 'O Lord, arise, help us, and deliver us for Thine honour.' None but Israel could call upon God's help as a right, on which depended His honour and name's sake, for when God made promises to Abraham, because He could swear by no greater, He sware by Himself. If we be only Gentile Christians, what a serious prayer to make.

In 1 Kings 8:22-53, at the dedication of the Temple, we find that Solomon used many of the petitions found in the Litany. Does not this suggest that the Litany of the Book of Common Prayer may have been taken from the old Temple Service Book? Again we pray: 'Mercifully forgive the sins of Thy people.'

THE COLLECTS, EPISTLES AND GOSPELS

THE Collects, Epistles, and Gospels are an entity, the object of which is to enable the Christian to study the binding thought which the compilers had in assembling them together in unity for national use Sunday by Sunday throughout the Church's year; so that when the people meet together on the Sabbath day for worship there will be unity of thought, which will promote unity of worship.

Not only should we sing praises with understanding, but there should be the same intelligent community of thought throughout the whole of our public worship. The greater the harmony, the greater will the power of the Master be felt.

By far the largest number of Collects have come down from very ancient times, the remainder having been composed by the reformers of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Scriptural, devotional, Christian, these short forms of prayer, as regards their literary language, terms and expressions, are as chaste, elegant and correct as their devotional spirit is pure, reminding us of the literary compilation of the Authorised Version of the Holy Bible.

Of the fifty-four Sunday Epistles, no less than thirty-nine are from that greatest of all theologians, St. Paul.

In these Collects, Epistles and Gospels, the Christian is afforded an annual panorama of all the chief facts, and all the chief truths of the Christian Faith. 'It is the peculiar computation of the Church to begin her years, and revive the annual course of her services, with this time of Advent. For she neither follows the sun nor moon to number her days and measure her seasons, according to their revolution; but Jesus Christ being to her the only Sun and Light, whereby she is guided, following His course alone, she begins and counts on her year with Him. When this Son of Righteousness therefore doth arise - that is, when His coming and incarnation are first propounded to us - then begins the year of the Church, and from thence are all her other days and times computed' (Dean Hook).

'The Christian year opens then on this Advent Sunday with a direct representation of our Lord Jesus Christ to us in His human nature, as well as His Divine nature, to be the object of our adoration. We cannot do otherwise than love the Babe of Bethlehem, the Child of the Temple, the Son of a Virgin, the Companion of the Apostles, the Healer of the sick, the Friend of Bethany, the Man of Sorrows, the Dying Crucified One; but we must adore as well as love; and recognise in all these the Triumphant King of Glory who reigns over earthly Sion, and over the Heavenly Jerusalem' (Dr J.H. Blunt).

The wonderful compilation of these Collects, Epistles and Gospels, suggest to the earnest Christian that holy men of old were moved and guided by the Holy Spirit of God. It seems that the unity and harmony portrayed in the arrangement of their order is beyond human power. The glorious Collect for Advent Sunday, the first Sunday of the Church's year, is so doctrinal as to epitomise the greater part of the Apostles' Creed, the central theme of which embodies the teaching of both Old and New Testaments, namely, the first and second comings of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ. How appropriate that our dear old Church — in existence in our land long before England was a state or name — should not only set aside the first season of the Church's year to teaching this central thought of the Scripture, but also at the same time declare this truth in the fourth of the 39 Articles of Religion. One of the outstanding facts in the history of the Church is that as soon as the teaching of the return of our Lord weakens so does the spiritual life of the people weaken accordingly, and they lapse into ritual and formality. The fact is potent in our day and generation, for the Church is gradually allowing herself to be overdecked in strange and ritualistic garments, foreign to her ideas and the practices of Apostolic times. In this, the first Collect of the Church's year, we are warned to cast off these works of darkness and to put on once more the simplicity of the armour of light.

A Collect that affords another identification mark that we are the people of the Book of Common Prayer is the third of those for Good Friday. This Collect should be used when ministers persist in teaching that the Jews and Israelites are one and the same, and that it does not matter which term is used. In this Collect we ask God to 'have mercy on all Jews, Turks, Infidels, and Hereticks, and take from them all ignorance and hardness of heart and contempt of Thy Word; and so fetch them home, blessed Lord, to Thy flock, that they may be saved among the remnant of the true Israelites.' This prayer in itself is conclusive evidence of a dividing barrier between the true servant people and the vast majority of Jews who are not of Israel. The British and Israel were thus regarded as one and the same people by the ancient ministry who, in Apostolic times, first addressed them. It would be perfectly natural for the ancient Britons to consider themselves to be Israel, as was so clearly taught by the services. Then, in course of time, amid the tumult of wars and revolutions, the knowledge of their origin became lost, and yet the people continued to proclaim themselves to be Israel, as the majority of those using the Prayer Book today do in the blindness and ignorance referred to in Romans 11:25.

The Epistles and Gospels are taken from the New Testaments with three exceptions, when they are taken from the Old Testament. This departure from the usual procedure should mark these occasions as of special importance.

The first is that of Ash Wednesday, when the Epistle is taken from the book of Joel (2:17), a portion of Scripture pleading with God's ministers to 'weep between the porch and the altar, and let them say, Spare Thy people, O Lord, and give not Thine heritage to reproach.' How appropriate that at the commencement of the Church's great annual fast, we should be reminded of the fast that God requires from His people. Truly 'who is blind but My servant.'

The next occasion is that for the Monday before Easter, when the Epistle is taken from Isaiah 63:1, which deals with the redemption of Israel. Shall we say that there is no design and purpose in reminding us, just as we are about to enter upon that great feast of the Atonement, how necessary the redemption of Israel is in God's scheme of things?

The third occasion is that for the twenty-fifth Sunday after Trinity, when the Epistle is taken from Jeremiah 23, commencing at the fifth verse — a portion of the Scripture dealing with the reign of a king of David's line, 'the Lord our Righteousness,' and the restoration of Judah and Israel.

Surely there is design and purpose in the fact that on the last Sunday of the Church's year our thoughts are turned to the one great event, the consummation and final ending of the Christian Age towards which we are so rapidly moving.

Another departure from the usual procedure is made on Easter Day. In the forefront of the Collect for that day there are three anthems to be used at the Morning service in the place of the Venite; and as we examine these anthems we find they are a commemoration of the Passover, Israel's deliverance from Egypt. If we be Gentiles, why commemorate, in our national service, an incident that happened in the history of a foreign people? Did not the compilers and revisers of our national worship know that we were the descendants of the people whom God delivered from bondage in Egypt, and did they not know that God commanded that people to keep the day of their deliverance for a memorial and a feast by an ordinance forever?

Exodus 12:1 : 'And the Lord spake unto Moses and Aaron in the land of Egypt, saying. . .' Verse 14: 'And this day shall be unto you for a memorial. . .' Verses 42-43: 'It is a night to be much observed unto the Lord for bringing them out from the land of Egypt: this is that night of the Lord to be observed of all the children of Israel in their generations. And the Lord said unto Moses and Aaron, This is the ordinance of the passover: there shall no stranger eat thereof' Verse 48: 'And when a stranger shall sojourn with thee, and will keep the passover to the LORD, let all his males be circumcised, and then let him come near and keep it . . .' What extraordinary testimony to our being God's chosen people Israel, for if we were Gentiles we should be breaking God's ordinance in defiance of His written word.

There is another ordinance coupled with the Passover that Israel must teach their children the deliverance from Egypt: 'And these words, which I command thee this day, shall be in thine heart: and thou shalt teach them diligently unto thy children, and shalt talk of them when thou sittest in thy house, and when thou walkest by the way, and when thou liest down and when thou risest up' (Deuteronomy 6:6-7). This is complied with in the Catechism in connection with the Ten Commandments, when the child is asked the question 'Which be they?' the answer given: 'The same which God spake in the twentieth chapter of Exodus, saying, I am the Lord thy God, who brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage.'

What effect would this have upon the minds and memories of children, with their simple faith and literal understanding? Naturally the impression would be that we were the people whom the Lord our God brought out of the land of Egypt! This commemoration of the Feast of the Passover raises another interesting suggestion. Is our Book of Common Prayer a revised version of the same form of worship Divinely given for use by the Israel people?

Let us take our minds back to the night before the Crucifixion, when we find our Lord gathered with His disciples in the upper chamber at Jerusalem, celebrating the Feast of the Passover. Whilst they were in the midst of eating the Paschal Lamb, Jesus took bread and wine and gave to the disciples, thus introducing the Christian ordinance of the Lord's Supper, now known as the Holy Communion. Why did Jesus take that opportunity of introducing the Christian ordinance of His Body and Blood and grafting it on to the Mosaic Feast? Does this not suggest that He was making the first revision of the Temple Service Book? Under Levitical Law the Feast of the Passover was part of the Temple worship, as much as our Holy Communion service is part of the nation's worship as established by the Law of this land. Our Lord made this alteration the night before He made that full and perfect sacrifice sufficient for all time.

So there need not daily, 'those high priests, to offer up sacrifice, first for his own sins, then for the people's: for this He did once, when He offered up Himself. For the law maketh men high priests which have infirmity; but the word of the oath, which was since the law, maketh the Son, Who is consecrated for evermore' (Hebrews 7:27-28). 'For those priests were made without an oath; but this with an oath by Him that said unto Him, The Lord sware and will not repent, Thou art a priest for ever after the order of Melchisedec' (Hebrews 7:21).

Under the Mosaic Law the priesthood was vested in the House of Aaron, and not the House of David, from which Christ came: 'If therefore perfection were by the Levitical priesthood (for under it the people received the law), what further need was there that another priest should rise after the order of Melchisedec, and not be called after the order of Aaron? For the priesthood being changed, there is made of necessity a change also of the law' (Hebrews 7:11-12). God alone can make a change in the Law; He has never delegated to man the privilege of making laws. Does this not suggest that this change in the Law was made when Jehovah Jesus did away with the Mosaic Feast, and introduced in its place the Christian ordinance of the Lord's Supper, thus making the first revision in the Temple Service Book? The remainder of the revision was most probably carried out by the Apostles, hence 'The Apostles' Creed.'

The Temple Service Book was part of the Law of the land, as much as our Book of Common Prayer is. Christ said that He had not come to do away with the Law, but to fulfil it; and may we not say to enrich it, to bring it to a higher level to fit the needs of the Christian Age? If God saw the need to provide the nation with a form of worship in the old dispensation, surely the same need would arise in the Christian Age? It is appreciated that there is no evidence to prove this, but as we have already seen, the use of our Book of Common Prayer can be traced back to the time of the Apostles themselves; and we read in the early days, after our Lord's resurrection, the disciples were continually in and out of the Temple praising God. If, then, the Temple Service Book had been done away with by our Lord, why did the disciples go to the Temple to worship? If a new order of service was introduced by our Lord, surely they would have used it in some place other than the Temple. True, this is only circumstantial evidence, and may not be convincing at all, but such evidence is used at the present day in our courts of law, so why should we be denied its use?

The Christian Age is the age of faith, and it seems that concrete evidence has been purposely withheld by God, so that during this age we should walk with the eyes of faith.

THE HOLY COMMUNION

THIS is the most beautiful and wonderful of the many services of the Book of Common Prayer. Divinely inspired? Most assuredly, for it was instituted by our Lord Himself the night before His Crucifixion! An Israel service? Most certainly! At the very commencement worshippers are called upon to recite the Ten Commandments, reminding them of the solemn and awe-inspiring scene at Sinai, when God descended from the Mount and spake in audible voice to the trembling people, all the words of the Law; thus burning into the very souls of the people that revelation of Himself which has not vanished all down the ages.

Notice, however, that after reciting the Ten Commandments, the people call upon God to write all these laws in their hearts. The appeal, then, in this generation, is not to that awe-inspiring scene at Sinai, but to that other awe-inspiring scene at Calvary. We pray God to put into force that New Covenant, sealed by the Blood of Jesus, foretold in Jeremiah 31:31 and restated in Hebrews 8:8-11.

In the Collect for the Queen, we pray that 'she may study to preserve Thy people committed to her charge.' The prayer for the Church Militant is one which the ministers of the Church would do well specially to notice; in fact, all Christians would do well to study the deep and important wording of this prayer, for here we have the solution to all our unhappy divisions. To quote just a small part of it : '. . . And grant that all they that do confess Thy holy name may agree in the truth of Thy holy word, and live in unity and Godly love.' Then further on we make allusion that we are God's people in the words 'And to all Thy people give Thy heavenly grace.' Thus through the many and beautiful prayers of this holy service the earnest Christian is led into the very presence of God, and as one approaches the Lord's Table how fitting is the thought behind the prayer left to us by the late Dr. Goard: 'Guilty before Thy Throne I stand, on me the doom abides, 'tis just the sentence should take place (the soul that sinneth it shall die). 'Tis just, but, O my Lord hath died, died for me, yea, died as me; took upon Himself my personality, and so fulfilled for each, the Eternal Law of Righteousness. . . The Soul that sinneth, it shall die. . . .' As we kneel at the Lord's Table we should try to feel that Jesus Himself is ministering to us; that it is the Lord's hands placing the bread in our hands — 'This is My body;' and that it is the Lord's own hands pressing the cup to our lips — 'This is My blood.' So shall we feed on Him in our hearts with thanksgiving, and be satisfied. Truly it is a wonderful and most sacred service.

SOLEMNISATION OF MATRIMONY

IS it merely a beautiful thought that the symbol of the union of Isaac and Rebecca is held out to the bridal couple as the pattern marriage union? Is there no purpose or design behind it? If we were only Gentile Christians the story of Isaac and Rebecca would be of no interest to us, The compilers and revisers of our Book of Common Prayer, however, surely knew that the marriage of Isaac and Rebecca was a great event in the ancient history of our people, that we are the descendants of that miraculous birth, the seed of Isaac. This is made clear as we read on in this service, for the minister prays: '. . .O God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, bless these Thy servants.' After the ring has been placed on the bride's finger, the minister prays: '. . . that as Isaac and Rebecca lived faithfully together, so these persons. . .' The very last words of the service read: 'For after this manner in the old time the holy women also, who trusted in God, adorned themselves, being in subjection to their husbands; even as Sarah obeyed Abraham, calling him Lord; whose daughters ye are so long as ye do well, and are not afraid with any amazement.'

A COMMINATION

THIS service contains special prayers for use on the first day of Lent. They are Israel prayers, and would be mostly devoid of meaning if used by purely Gentile people.

After referring to the discipline which attained in the Primitive Church at the beginning of Lent, the minister says: 'It is thought good, that at this time (in the presence of you all) should be read the general sentences of God's cursing against impenitent sinners, gathered out of the seven and twentieth chapter of Deuteronomy.' A little later the minister, after appealing to the people to be penitent, says: 'This if we do, Christ will deliver us from the curse of the Law.' Following this is the fifty-first Psalm, where in verse 18 we say: 'O be favourable and gracious unto Sion; build thou the walls of Jerusalem.' The service concludes by all repeating the following Israel prayer: 'Turn thou us, O good Lord, and so shall we be turned. Be favourable, O Lord, be favourable to Thy people who turn to Thee in weeping, fasting and praying. For Thou art a merciful God, full of compassion, longsuffering, and of great pity. Thou sparest when we deserve punishment, and in Thy wrath thinkest upon mercy. Spare Thy people, good Lord, spare them, and let not Thy heritage be brought to confusion; Hear us, O Lord, for Thy mercy is great, and after the multitude of Thy mercies look upon us; through the merits and mediation of Thy blessed Son, Jesus Christ, our Lord, Amen.' Then follows the blessing: 'The Lord bless us, and keep us; the Lord lift up the light of his countenance upon us, and give us peace now and for evermore, Amen' (cf. Numbers 6:23-27).

A FORM OF PRAYER WITH THANKSGIVING

THIS is appointed for use once every year upon the anniversary of the day of the accession of the reigning sovereign. In the prayer book in use in the early part of Queen Victoria's reign there appears a remarkable prayer. After making petitions for Her Majesty's welfare, the prayer ends with these wonderful words: 'And that these blessings may be continued to after-ages, let there never be one wanting in her house to succeed her in the Government of this United Kingdom, that our posterity may see her children's children, and peace upon Israel. So we that are Thy people, and sheep of Thy pasture, shall give Thee thanks for ever, and will always be showing forth Thy praise from generation to generation.' Again we say: 'Who is blind but my servant? . . .' They do not appear to have been blind in Queen Victoria's time. These words were, however, erased before the end of her reign.

Can there be any doubt that in times past our forefathers were well aware of their Israelitish origin, and that they were indeed the people of the Book of Common Prayer, as much as they were the people of the Holy Bible? Although this fact has been largely lost sight of in our day and generation, evidence is not wanting, as instanced in 1928 when 'The Revised Prayer Book' was submitted to Parliament and rejected by them, that deep down in the hearts of the people of Britain is the sub-conscious fact that the Book of Common Prayer is one of our most treasured heritages and not to be interfered with lightly. One would have thought that that would have been a warning to those to whom the custody of our great heritage has been committed. But apparently this has gone unheeded, for newspapers have since announced that a number of bishops seek power to be allowed to make alteration in our glorious book without the sanction of Parliament. This means that they are seeking to do away with the authority of the Sovereign as Supreme Governor and head of the Church, and so ultimately open the way to introduce those pagan practices which were eradicated at the Reformation.

If we can see that our Book of Common Prayer has been founded on the pure Word of God and zealously guarded by holy men of God all down the ages, what need is there to make fundamental changes? If here it has been shown, however imperfectly, that there is a Divinely-designed purpose behind our Book of Common Prayer, what authority have bishops to interfere with that purpose? It is the duty of all lovers of this glorious book to be watchful and hold fast to this great heritage; for, as we have already seen, the design and purpose of the Book of Common Prayer fits so accurately with the one great plan, as outlined in the Holy Bible, the ultimate aim of which is to bring the whole world under one Kingdom. We are either of Israel by descent or we are Israel by adoption, for, as St. Paul says: 'If ye be Christ's then are ye Abraham's seed and heirs according to the promise' (Galatians 3:29). Christ came to confirm the promises made to the fathers (Romans 15 :8). Christian, of whatever race you may be, if indeed ye are in Christ, then you are one with Israel, and are privileged to inherit the blessings and to share in the responsibilities of the Covenants. How God's promise to Abram rings out: 'And in thee shall all the families of the earth be blessed' (Genesis 12:3). As we study the Book of Common Prayer in the light of the Israel identity teaching, viz. the teaching of the Holy Bible, what a sincerity comes to our worship, as we realise and join in the true meaning of its beautiful prayers and praises.

Many who have been blessed with this teaching as God's purpose have confessed to a new and wonderful vision when they join in the service of the Book of Common Prayer week by week in our National Church, creating in the hearts and minds of earnest Christians a renewed desire to enter into that fuller and higher life that Jesus offers to all who believe on His Name.

When we pray that prayer in the Communion Service after the bread and wine has been taken: 'And here we offer and present unto Thee, O Lord, ourselves, our souls and bodies to be a reasonable, holy, and lively sacrifice unto Thee;' asking God to accept 'this our bounden duty and service' (Romans 12:1-2), we realise that through the blessings of the Atonement we have been made sons of God (1 John 3:2), and that our bounden duty and service is to offer ourselves to God for service, no matter how humble and trivial our part may be in the establishing of His Kingdom upon the earth; taking our share in bringing to fruition that age-long purpose of our Heavenly Father, the consummation of which is to bring the whole world into one great family, and that an Israel family, and God the Father of all.

'And I John saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a great voice out of heaven saying, Behold, the tabernacle of God is with men and He will dwell with them, and they shall be His people, and God Himself shall be with them, and be their God' (Revelation 21:2-3).

APPENDIX 1: The Sabbath Day

The references in the present booklet to the 4th Commandment regarding the Sabbath and its observance require some note of explanation for Christians. The primitive Christians for the most part continued to keep the seventh day as a day of rest and prayer, as would naturally be the case since the first Christians originated in Palestine, where the very strict observance of the Sabbath prevailed. Indeed we can see from the Gospel accounts of the differences between Our Lord and the Pharisees over this subject how strict had become the rules regarding Sabbath maintenance.

However, as Jesus Christ had risen from the dead on the first day of the week, it was inevitable that this should be kept as the Lord's Day, (Revelation 1: 10). This difference from the ancient ordinance was only natural in view of the new Christian dispensation. Various forms of Sabbatarianism have at times prevailed in western Europe, e.g. certain Acts of the Commonwealth Parliament in England enjoined an observance so strict that even a walk was prohibited on the Sabbath. In Scotland, in the 17th and 18th centuries, no book or music except religious in nature was permitted.

The term Sabbath is used in Protestant countries as synonymous with Sunday, but the latter is to be preferred since Sunday being the first day of the week is that of the Lord's Resurrection, to be hailed with joy and not gloom. It is noticeable, however, that a writer of the 12th century, Peter Abelard in a hymn well known in an English translation, uses the term Sabbath as synonymous with Sunday.

APPENDIX 2: The Calendar

At the beginning of the Prayer Book, there is a Calendar of Lessons to be used at each service, arranged so that during the course of one year the Bible is read through once. The Psalms are also read once each month and there are some lessons for certain days taken from the Apocrypha. These lessons were set forth in their entirety in AD. 1552 and the proof of their inspiration is that these lessons have continued to speak to the nation over the years in concert with great national events.

It is a sad reflection on the National Church that as the Prayer Book has fallen into disuse during the critical phase of our Age-end history, the Word of God unto the people has ceased to be heard in the nation-state. Without the understanding of the true relevance of the Scriptures to our national life, the nation has been deceived and has followed in the pathways of defeat and destruction.

A classic example of this was evidenced on 28th October, 1971, when the British House of Commons voted in favour of a 'decision in principle' to accept the Treaty of Rome and Britain's entry into the Common Market. The Prayer Book reference for this Proper Holy-Day, St Simon and St Jude, in the First Lesson for Morning Prayer is Isaiah 28:9 to 17. These verses contain a powerful condemnation of the rulers of the nation that make a 'covenant with death' making lies their refuge to hide, as we would say today, their hidden agenda. Alas for the poor nation, this Word of God was not heard as a witness to those who voted on the evening of that day to betray the covenants made by God with His People Israel.

The most wonderful witness to the inspiration of the Prayer Book lessons was confirmed at the liberation of Jerusalem by British Forces in 1917. General Allenby, who was in command of the Palestine Campaign, commenced his attack — which resulted in the deliverance of Jerusalem — on 18th November, 1917. The First Lesson for Morning Prayer of that day is taken from the Apocrypha Baruch 4:36 through to the end of the 5th chapter. The prophecy concerns the joy that is coming to Jerusalem at the hand of Israel's sons of the great dispersion of the servant people.

Jerusalem surrendered without a shot being fired early on 9th December, 1917 and the lesson for the previous day is Isaiah 31 which includes verse 5; 'As birds flying, so will the LORD of hosts defend Jerusalem: defending also he will deliver it; and passing over he will preserve it.' In exactly that way was Jerusalem taken as the Royal Flying Corps passed over Jerusalem and without attacking the city struck fear into the Turks. It is remarkable also that the motto of No.14 Bomber Squadron involved in these overflights is 'I spread my wings and keep my promise.'

The General set 11th December as the official entry into the captured city, while the day before was a rest day. The First Lesson for Evening Prayer on 10th December is Isaiah 40:1 to 12 which begins with the words; 'Comfort ye, comfort ye my people, saith your God. Speak comfortably to Jerusalem, and cry unto her, that her warfare is accomplished. . .'

On 11th December when General Allenby entered Jerusalem on foot, having dismounted from his horse to lead the host (the Israel-British soldiers), the First Lesson for Morning Prayer included the promise from the latter part of Isaiah 40; 'They that wait upon the LORD shall renew their strength;' while the First Lesson for Evening Prayer is Isaiah 41:1 to 17 which begins; 'Keep silence before ME, O islands and let the people renew their strength' (eleven months exactly prior to the Armistice in remembrance of which the eleventh-hour 'silence' was observed).

There could not be a more appropriate day than 11th December on which we might assemble in our places of worship to render unto the Lord the honour due unto His Name and to hear the words of the lesson from Isaiah 41; 'But thou, Israel, art my servant, Jacob whom I have chosen, the seed of Abraham my friend. Thou whom I have taken from the ends of the earth, and called thee from the chief men thereof, and said unto thee, Thou art my servant; I have chosen thee, and not cast thee away.'

The name 'Jerusalem' has the meaning of a 'foundation of peace' or 'civilization of peace.' With the deliverance of historic Jerusalem by the forces of Britain-Israel in December 1917 without a shot being fired or any stone or building being thrown down and with the unpretentious entry of General Allenby on foot the nation was given a sign, not of the coming of the Jewish Israeli state, but of a time yet further when prophetic Jerusalem would be liberated from Gentile systems and influence. Indeed, to a time when the people of reformed Israel in the West would go out to welcome the Great Commander of the host and armies of the Israel nations - our Lord Jesus Christ.