Our First Ancestors

Were our first ancestors civilised or uncivilised? Did they wander

constantly and hunt and fight for a living? Could they write?

Modern science once thought it had the answer to those questions, and

the answer, science said, was that our first ancestors were the most

ignorant of barbarians.

But the recent findings of archaeologists have altered this concept.

Dr. WW Bell-Dawson, a Canadian scientist has this to say in his book, The

Bible Confirmed by Science:

'Neither in Egypt nor in Babylonia has any beginning of

civilisation been found. As far back as archaeology can take us, man is

already civilised, building cities and temples, carving hard stone into

artistic form, and even employing a system of picture writing. And of

Egypt it may be said the older the country the more perfect it is found

to be. T'he fact is a very remarkable one, in view of modern theories of

development, and of the evolution of civilisation out of barbarism. Such

theories are not borne out by the discoveries of archaeology. Instead of

the progress we should expect, we find retrogression and decay; where we

look for the rude beginnings of art, wefind an advanced society and

artistic perfection. Is it possible that the Biblical view is right

after all, and the civilised man has been civilised from the

outset?"

Archaeology Versus Evolution

WW Prescott, in his book, The Spade and the Bible, says:

'Not a ruined city has been opened up that has given any

comfort to unbelieving critics or evolutionists. Everyfind of

archaeologists in Bible lands has gone to confirm Scripture and confound

its enemies'. '

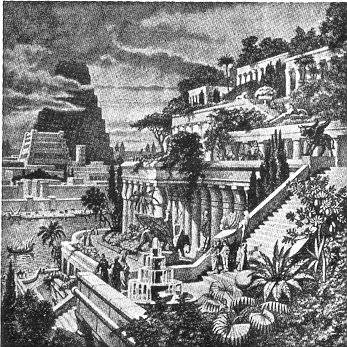

Life in the early ages centred around the temple. All the temple

towers of early Babylonia were of the same design; a series of vast,

almost square platforms rising one above the other, with stairways

leading up. The shrine of the god was on the top.

The Ziggurat at Ur had three platforms, some had as many as eight.

The shrine at the top was in blue glazed brick with a golden metal roof.

The Babylonian word ziggaratu means, pinnacle on top of mountain. The

theory that the ancient conquerors of these plains, in remote ages, were

mountaineers who, either from homesickness or from religious

conservatism, or both, wished to worship their god on the high places,

as they had always done. In Chaldea they had to make the high places

with their own hands, and the account of the building of the tower of

Babel could be the record of such an event.

In Genesis 11:2-4 we read, "And it came to pass, as they

journeyed from the east, ... they said one to another, Go to (come), let

us make brick, and burn them thoroughly. And they had brick for stone,

and slime had they for mortar And they said Go to, let us build us a

city and a tower, whose top (may reach) unto heaven, ... '

These temples were not merely places of worship - about their courts

were store-houses for the tithes and offerings brought in by the

faithful worshippers, or paid as rent by tenants of the sacred estates.

There were living quarters for the priests and the temple servants.

There were workshops and factories where the men and women attached to

the temple were employed, spinning and weaving into cloth the wool which

the farmers brought, casting and hammering into art objects the copper

and silver paid as tithes by the merchants of the city.

Exhaustive accounts were kept of what was received and what was

disbursed. Immense cattle yards were kept where the livestock given to

the temple were cared for. They found contracts setting forth their

responsibilities and regulating their profits - documents referring to

granaries, freight boats, etc.

The temple stood in relation to the people as the State does in

modern times, and the records here are of administration. They show an

efficient and well-organised community Each person had a cylinder seal,

they were rolled across the wet clay and used in place of a signature.

These seals are very small, some only -5/8ths of an inch long. It took

great skill and very tiny tools to carve on this small cylinder. Various

semi-precious stones were used, one of gold was found in the tomb of a

queen. About 3,750 BC, the art of the seal reached perhaps its highest

expression. They carved figures whose physical characteristics were

emphasised realistically, and at the centre of the composition there was

a panel containing an inscription. One shows a bearded hero watering

buffalos from a vase out of which flow two streams, then it shows water

and a rock border at the bottom. The inscription names Ibnisharrum,

as the owner of the seal, and dedicates it to Shargalisharri

king of Akkad. He was a grandson of Sargon, descendant of Ham.

This whole scene was on a cylinder seal less than an inch long. No

modern jewel engraver could do better.

Because it is difficult to imagine life other than in terms of that

which we know, after death they assumed that their occupations and needs

would be similar, that the next world is a continuation of this one.

Whatever a person used in their lifetime they will use after death. The

woman takes her spindle, her needle, her mirror and her cosmetics. The

carpenter takes his saw and chisels, the soldier his weapons of war. The

king must be provided with a goodly sample of his pomp on earth. It is

not surprising then that the archaeologist derives most of their

material from the cemeteries of the old world, and what they find

illustrates not only their beliefs and burial customs, but also their

everyday life.

From the Royal tombs at Ur dating about 3,000 BC. come some very

beautiful things. The famous gold dagger of Ur, a weapon whose blade is

gold, its hilt of lapis lazuli decorated with gold studs, and its sheath

of gold filigree work. With it was another object scarcely less

remarkable, a cone shaped container of gold, ornamented with a spiral

pattern and containing a set of little toilet instruments, tweezers,

lancet, and pencil also of gold. The royal graves all have a harp. The

most magnificent yet found has a sounding-box bordered with a broad

edging of mosaic in red, white and blue. The two uprights were encrusted

with white shell and lapis lazuli and red stone arranged in zones

separated with wide gold bands. Shell plaques engraved with animal

scenes adorned the front, and above these projected a splendid head of a

bearded bull wrought in heavy gold, with a lapis lazuli beard.

Queen Shubad on her deathbed wore an ornate headdress made of a long

gold hair ribbon covered by beaded wreaths with gold pendants, heavy

earrings of gold and a golden Spanish type comb with five points ending

in lapis centred flowers of gold. By the side of the body lay a second

headdress. On a diadem made of soft white leather had been sewn

thousands of minute lapis lazuli beads, and against this background of

solid blue were set a row of exquisitely fashioned gold animals, stags,

gazelles, bulls and goats, with between them clusters of pomegranates,

three fruit hanging together shielded by their leaves.

There is a helmet of beaten gold made to fit low over the head with

cheek-pieces to protect the face. It was in the form of a wig, the locks

of hair hammered up in relief, the individual hairs shown by delicate

lines. The ears are rendered in high relief and are pierced so as not to

interfere with hearing. Sir Leonard Wooley, who headed the excavation at

Ur said, "As an example of the goldsmith's work this is the

most beautiful thing we have found, and if there were nothing else by

which the art of these ancient Sumerians could be judged we should

still, on the strength of it alone, accord them high rank in the roll of

civilised races."

The contents of the tombs illustrate a very highly developed state of

society. A society in which the architect was familiar with all the

basic principles of construction known to us today. They commonly used

not only the column, but the arch, the vault, and the dome.

Architectural forms which were not to find their way into the western

world for hundreds of years. The craftsman in metal possessed a

knowledge of metallurgy and a great technical skill. The merchant

carried on a far-flung trade and recorded their transactions in writing;

the army was well organised and victorious, agriculture prospered, and

great wealth gave scope to luxury.

We do not mean that all the world had a high culture for basically

only those nations who have it now, had it then. Sir Charles Marston in

his book, The Bible Comes Alive! says, 'All stages

of civilisation exist today throughout the world, and so far as we are

aware, always have existed. And where glorious monuments certify to a

great past, those who now dwell around them often testify to a great

decay.' The old truths of the Bible, which are ever new, will

abide. Like their Author, they are "the same yesterday, and today,

and forever" They cannot be shaken. Current world history is

fulfilling its prophecies. Its truth is written on the ruins of earthly

kingdoms. Neither the Bible nor Babylonian excavation know anything of

uncivilised man. Life at the beginning of civilisation, was simple but

cultured, due to the influence of the Adamic people.